by Dan T. Neely

When we think about Irish music and politics, we typically think of songs from the Republican tradition. However, they say that “all politics is local,” and with so much of the early Irish recording industry happening in New York, it’s possible to find evidence of local politics, and in the case of the Flanagan Brothers, specific political affiliation.

Mike’s granddaughter Eileen once told me that her mom Ellen, Mike’s daughter, remembered “You Can't Keep A Good Man Down,” which the Flanagan Brothers recorded for Columbia in 1928, as one of the songs of Smith’s 1928 presidential campaign. A paean to Smith, the song states:

It would be only just and fair

To help him get the Chair

Then the east side, west side

Will go dancing round the town

Oh, USA will have Al some day

You can’t keep a good man down

Eileen even managed to find evidence of the brothers playing at a rally in support of Al Smith’s 1928 campaign bid in Philadelphia, adding to what we know about where they performed. His daughter Kathy remembers hearing stories about him riding in a limousine to Philadelphia.

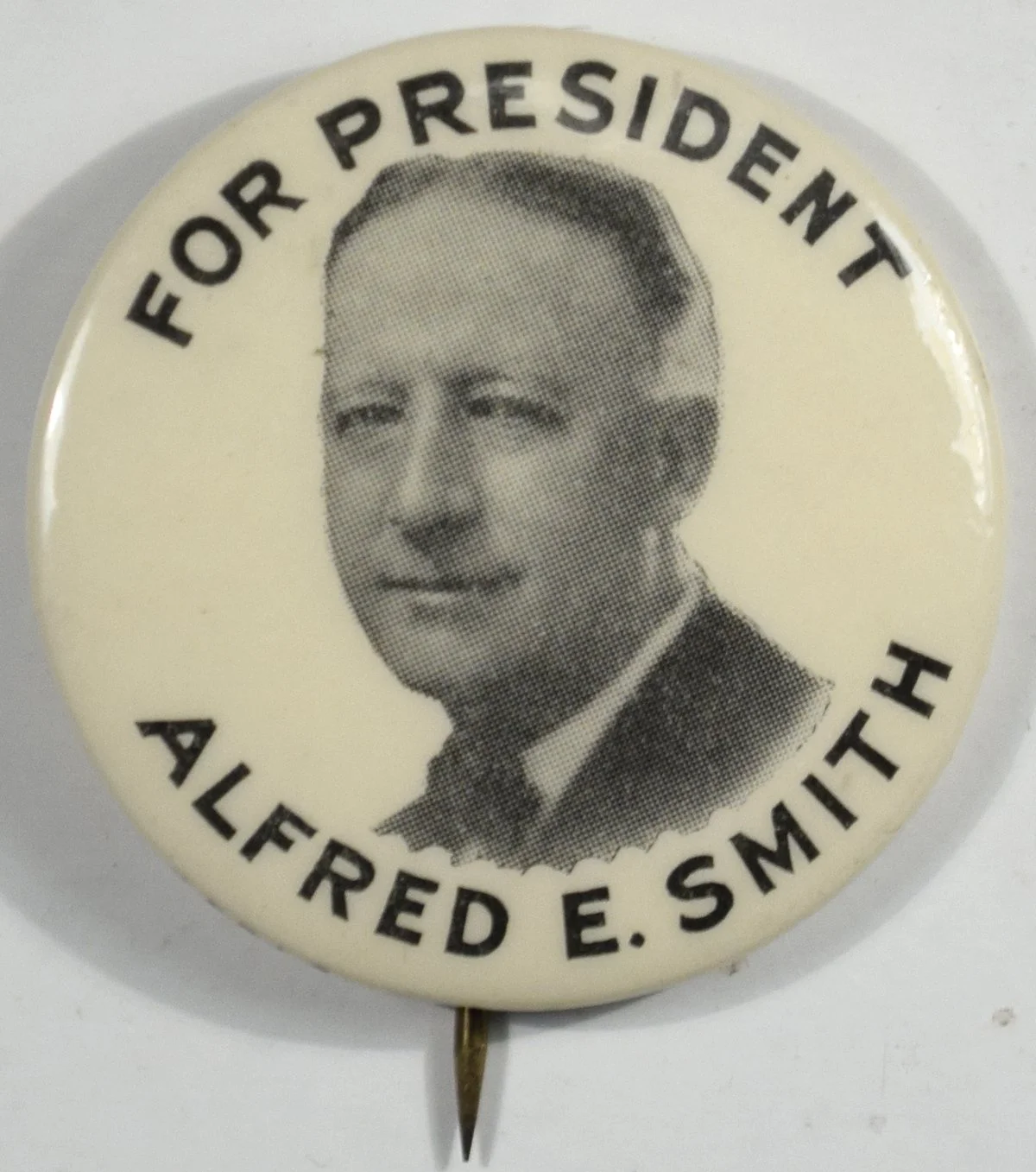

In the 1928 presidential election, Smith, a Democrat and the then-governor of New York, ran against Herbert Hoover. The two made a fascinating contrast. Smith, on the one hand, represented urban America. He was Catholic, pro-immigrant, and an outspoken opponent of prohibition. Hoover, on the other hand, was a Quaker, a devout, moralistic man and a product of rural America who fashioned himself the “peace and prosperity” candidate. It was a particularly vicious election and one that Hoover ended up winning in a landslide.

Part of Smith’s campaign strategy, though, targeted ethnic urban neighborhoods. Despite his campaign’s disappointing outcome, it was a successful approach that brought Jewish, Italian, Polish, and especially Irish immigrant communities of these areas largely to Smith’s side.

Music seems to have been an important part of how Smith (and really, lots of other politicians) attempted to mobilize to the Irish community. We know he had an early close relationship with Irish song and had a particular affection for the work of the great Ed Harrigan, a founding father of modern musical theatre. According to historian William H.A. Williams, Smith was Commodore of the Harrigan Club, “a banqueting, drinking, and singing society that included a number of prominent New Yorkers, especially politicians” (Williams 271, n.20). In his work, Williams mentions that some of Smith’s favorites from the Harrigan repertory were “Danny By My Side,” from Last of the Hogans (1891) and “Babies on Our Block” from The Mulligan Guards (1879), a pair of songs from shows that recognized and celebrated the Irish-American working class. Popular Irish ditties from vaudeville and tin pan alley that recognized Irish-American identity, Harrigan and beyond, were the stuff that helped tie the local saloon to Tammany Hall.

The music the Flanagan Brothers recorded in 1928 reflects this kind of musical taste. A bit of background here: although Joe and Mike first went into the studio in 1921, it wasn’t until 1926 that the duo first put their voices to record. The songs they recorded in 1926 and 1927 were generally of a comic nature and were sometimes worked into novelty sketches. This type of material continued into 1928 with examples including “Kelly’s House Party,” “Brian O’Lynn,” “Let Ye All Be Irish Tonight,” and was common until their final recording sessions in 1933, when they recorded the “Half Crown Song” (Co 33528).

But in 1928, Joe and Mike began to recorded pro-Irish songs like “Ireland's 32” (Co 33230), “Flanagans At St. Patrick's Parade” (Co 33230), and “The I.R.A.” (Co 33243), each of which expressed a more conspicuous awareness of Irish Identity in America and of politics in Ireland. It was a new direction.

In addition, Joe and Mike recorded a number of popular Irish songs that reflected a more directly political direction, including “The Sidewalks Of New York” (Co 33233) and “You Can't Keep A Good Man Down” (Co 33263). “You Can't Keep A Good Man Down” wasn’t just an extolment of Smith for the campaign trail but, it was melodically related to “The Sidewalks Of New York,” Smith’s theme song, which the Flanagans also recorded in 1928 (Co 33233).

In addition, although it was an old vaudeville number, “Sweet Rosie O’Grady” (Co 33233) the B-side to “Sidewalks,” was also associated with Smith. So much so, in fact, that Gosch & Hammer in their 2013 book The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, quote the gangster years later as saying "a guy like Al Smith, he's a 'Sweet Rosie O'Grady' kind of guy – like the guys we grew up with.” These tracks show the Flanagans were all-in on Smith and his campaign, and were making an effort to cover all their musical bases, including the saloons, Tammany Hall, and everywhere in between.

But wait! There’s more! The day the Flanagans recorded “You Can't Keep A Good Man Down” was also the day they cut “Kelly’s House Party,” the focus of our last post. Looking back at that tune, we find the Flanagans again down the Al Smith rabbit hole. The songs being sung there? Popular songs from Irish-America, the sort that would have been welcome in Smith’s campaigning. That sly reference to “Hennessy V.S.”? It’s a nod towards Smith’s anti-Prohibition stance.

But here’s where it gets even more interesting: the “Jim Egan” that dances a step as Joe plays away? He recorded three solo sides on the very same day “Kelly’s House Party” was recorded: “The Daughter Of Rosie O’Grady” (Co 33354), a song about a working class Irish girl derived from “Sweet Rosie O’Grady” (and a song that Bugs Bunny sang in the 1947 cartoon “A Hare Grows in Manhattan” in a scene that seems to play on a nostalgia for Smith and a New York of yore); “Little Annie Rooney” (Co 33259), a song popularized in 1890s New York by Annie Hart, known as “The Bowery Girl,” that is also the title of a 1925 silent feature about an Irish girl growing up in the slums of New York (the song also happens to appear as part of a medley in the 1935 Max Fleischer cartoon “Musical Memories,” immediately after the Al Smith caricature sings a verse of “Sidewalks of New York” https://youtu.be/-geoILmqpRY?t=117); and finally, “Al Smith” (Co 33259), another paean to the man they say they couldn’t keep down: